Categories: all aviation Building a Biplane bicycle gadgets misc motorcycle theater

Fri, 04 Mar 2022

The End of an Era (and the Beginning of Another)

As I write this, I am sitting in a cut-rate motel near Lakeland, FL. I have finally seen, in person, my new airplane. It is lovely. It is a biplane. It is a Marquart Charger. I'll take a test flight tomorrow, and sign all the documents to make it mine.

I knew when I bought Norbert the Champ that it wouldn't be my airplane forever. I knew it was something of a starter plane, though I didn't have a specific path forward in mind. I kind of figured I'd end up selling it to get an IFR-capable plane, so I could get my instrument license to facilitate flying down to visit my parents more often.

The thought of replacing it with a Charger is pretty damn cool.

But it brings to mind all the neat stuff I've done with Norbert. We flew to Oshkosh, spending three weeks traveling most of the way across the country, and seeing the world's biggest airshow. That was 2019. Before that, in 2017 and 2018, we did two big trips to California, one of them to visit my brother in LA, the other to visit my cousins in the Bay Area, and my friend Alex in Humboldt.

I've taken Norbert up to the San Juan islands more times than I can count. I've flown many friends (though not lately), taking them up for a little trip somewhere (out to the northwest tip of the state, at Quillayute, or up to the islands, or down to Olympia to pick up a friend just so we could go up to Port Townsend for pie). So much pie. I have eaten so much Spruce Goose Cafe pie because of Norbert.

In many ways, it is an ideal little plane for me. It's small and unimposing. It's slow, but also docile and forgiving, and kind when the pilot might not be the most coordinated klutz in the sky. It's classy looking, in its way, with the poorly conceived but very attractive black and green dope (lovely to look at, but exactly the same colors as the scene of a crash in so many places around the PNW where there are trees, making perfect camouflage; the opposite of what you want in a rescue situation). It's very well-equipped, now that I've had my nefarious way with it: a new ADS-B transponder, a new radio, and a new engine monitor, plus it's been well kept up and stored in a very protected hangar. I like to think, even electronic toys aside, that I'm selling it on better than I found it.

For that is the final calculus: I must sell Norbert the Champ. I'll have a for-sale page up soon. I can't afford to keep two airplanes, so the old one has to make space for the new one. It's been a very good plane for me, and I will always regret letting it go, but I would also regret letting this new Charger get away, and it offers me a great set of new opportunities, chief among them having an actual living, breathing Charger to examine to see how it's built; and giving me the opportunity to build up hundreds of hours on a Marquart Charger, making the first flight of the Charger I'm building much less of an Event than it might otherwise be.

So it is with great fondness that I consider this to be the final days of my time with Norbert the Champ. We've done wonderful things together, and I know you will go on to the next owner who will discover all the wonder and happiness to be had by puttering about the sky at a leisurely 85 MPH.

Posted at 17:49 permanent link category: /aviation

Mon, 07 Feb 2022

The weather was stunning yesterday, so I ended up taking a lot of pictures when I flew to Friday Harbor. I laid them all out in a sort of photo essay. Enjoy!

A Lovely Flight to Friday Harbor One Sunday

Posted at 11:54 permanent link category: /aviation

Tue, 14 May 2019

Norbert the Champ has been ailing a bit in the last few months. I've been flying every few weeks, as the weather allows, occasionally letting a whole month pass between flying dates. The problem is, when the engine sits like that for long periods, it gives condensed water a chance to attack the innards and start creating rust.

The accepted remedy for this problem is to fly more often (how convenient!). The idea is that by flying, you warm up the oil, and encourage the water to evaporate out, as well as getting a fresh coat of oil in all the places it's supposed to be. Ideally, you want the oil to be 180-200°F for at least half an hour to get the water out.

Fortunately, I haven't noticed Norbert's ailment in the sense of feeling like anything's wrong as we fly. Rather, I've been noticing that the crankcase breather tube is drooling a bit of oil/water mixture after flights. I'll come back a week or so later, and there's a 2" pool of mocha-colored oil-water emulsion sitting under the engine, almost exactly like it had a little potty training accident.

The plane is equipped with an air-oil separator, which is a little thing the size of a beer can which is supposed to condense the oil out of the crankcase breather tube, and let it drain back to the oil tank, rather than sending it out over the belly of the plane in flight. It seems to work pretty well, but this new pool of oil was worrying.

Did it mean the separator needs to be cleaned? Did it indicate some other problem inside the engine? The oil on the dipstick came out looking like oil (good) and not like mocha foam (which would be bad), so I wasn't sure.

Finally this last weekend, I got a chance to chat with the local mechanic about it, and his recommendation was to go fly the plane a bit to warm up the engine, then do a compression test. This would confirm whether any of the cylinders were leaking more than they should. Previous compression tests (we do one at least every year) have been good, but this one showed that the #4 cylinder was down a little bit. Apparently the ideal number is 79 out of 80, with a full 80/80 indicating a problem, and anything down to about 40/80 being in the acceptable range (this is hard for my perfection-oriented brain to comprehend, but apparently is true).

After the compression test, the A&P mechanic said, "Frankly, what I'd recommend is that you go out and fly for a while at higher power, like a high-power cruise. That'll probably improve this, though even 72/80 is pretty good." This actually aligned well with my thoughts on boiling the water out of the oil, so I set out to see what I could do.

Norbert and I launched into the warm May day (it was over 80°F that day), and I set out to fly it like I basically never do.

The first order of business was not to climb too high. Normally I'm in the "altitude is insurance" game: the higher you are, the more gliding distance you have if anything goes wrong with the engine. However, the air is thicker and hotter down low, so I mentally plotted a course over a set of flat fields through the Snoqualmie Valley.

The next thing was to push the engine faster than normal. I've settled on a fuel-sipping 2200 RPM cruise (2500 is the maximum, or nominally 100% power), which probably represents around 60-65% power. I've been burning about 5.5 gallons per hour at this setting, which seems like a nice level. I have no idea how much fuel we'd actually burn at higher power, but presumably around 8-10 GPH, which is a lot for a 90 HP engine on a plane like this.

So I launched from Harvey and aimed myself southeastwards. It was interesting to see what happened.

I set myself up for about 1700 feet of altitude, which puts me safely over the legal limit, but not so high that I was losing much heat from the ground-level air. I pushed the power until it was just shy of the 2500 RPM redline limit. The plane made a constant shimmy and judder feeling, very light, but enough to communicate to me that it wasn't happy. The louder engine noise combined with increased wind noise to give a sonic edge to the plane's discomfort. We ended up cruising around 105-110 MPH, vs. my normal 85 MPH at 2200 RPM. Gratifyingly, the oil temperature kept rising, finally stabilizing just below the 200°F mark -- I haven't seen over 150° since last summer. Maybe I have been under-working the engine.

I flew most of the way to North Bend, then turned around over Carnation and flew back, circling once over a friend's house, and then looped back around to Harvey Field. I briefly lowered the engine back down to 2200 RPM and let it settle into its happier cruise speed. It was remarkable how much more comfortable the plane felt. Then it was back up to nearly 2500 for the return to Harvey, and an uneventful landing.

In all, just shy of an hour's flight time, almost all of it spent at just shy of full power. Out of curiosity, I checked the fuel left in the tanks -- I'd taken off with around 21 gallons -- and found there were about 14 left. 7 GPH for nearly full throttle. I had expected more, and would probably plan on at least 8 if for any reason I had to fly for any distance at full throttle; part of my hour's flying time included taxiing on the ground. My fuel dipstick measurement technique is fairly crude, and will never be more accurate than within about a gallon or two (gas cans always seem come in frustrating "gallon plus 3 ounces" sizes to accomodate people mixing 2-stroke fuel, making accurate measurement very difficult).

I was able to visit the plane Tuesday night after the flight on Saturday, and found a small puddle of discarded oil, fortunately not as mocha-colored. There is a distinct trace of oil running down the belly, but it's coming from somewhere in the engine compartment rather than from the breather tube.

A very interesting experiment in Going Fast with my pal Norbert. My key takeaway is that I should probably be running the engine harder for its own good health. The slightly increased fuel burn is a fair trade-off for not having to overhaul the engine (a $25,000 proposition) early.

Posted at 22:21 permanent link category: /aviation

Sun, 21 Apr 2019

The Washington State Department of Transportation and a bunch of aviation organizations just released the Fly Washington passport program. Basically, it's a program where you get a free "passport" booklet which contains a bunch of blank spots organized by region of the state, and your job is to fly to different airports and fill out the passport. Apparently there's some kind of prize at the end if you fulfill a set of requirements.

The goal of the program is to encourage aviation, and particularly to drive traffic to smaller airports that have been suffering from lack of use in the last decade or two.

I'm here to tell you, I love this kind of thing. I always envied people who had passports full of visa stamps; there's just something so satisfying about all those stamps from all those places. It's not even the places that appeal to me, just the sheer collector-impulse OCD satisfaction of pages covered in stamps. So I fell for the Washington aviation version hook, line and sinker.

Despite what it says on the official page, it appears that most airport offices have at least a handful of passport booklets available. You don't have to go exclusively to the four official places to pick one up. I was able to get one at the Harvey Field FBO office, and they had a stack of at least ten more ready to give away. At least here at the start of the program, it's worth asking at your local airport.

Norbert at the Darrington Airport (1S2)

This weekend was my official entre into the passport stamp game. I managed to hit five different airports over two days -- yesterday I flew up to Lynden to visit a friend, and today I took the afternoon to specifically go out and collect some stamps, eventually stopping at Arlington, Darrington, Paine Field, and Harvey Field. I expect to have more days like this over the summer, where I just go flying for the day and hit new airports I haven't visited recently, simply to collect the stamp.

The thing is, from what I can tell, pilots will grab at nearly any excuse to go flying. It acts nearly like an addiction. "Gotta go collect some stamps" is a ready-made excuse, and seems to me like an excellent way to get a bunch of pilots into the air and visiting airports far and wide across the state.

On today's flight, I started out at Harvey as usual, and grabbed the stamp from the office, where it's temporarily being kept until they set up an external station for it. Then it was off to Arlington for my next stamp -- Lynden was collected yesterday. Arlington was interesting, because the wind changed direction as I was fuelling up, then Norbert's carb heat seemed to malfunction at the run-up check. I pulled back around to a taxiway, shut down, and did a quick visual check -- everything looked right, and on the next run-up it worked like it should. These little Continentals apparently ice up at the slightest provocation, so a malfunctioning carb heat system is a big deal.

From Arlington, I had to ponder where I wanted to go next. Norbert is still limited by a lack of blinkenlights, which keeps it from being legal for night flight, so I had to be back to Harvey before the sun set. That ruled out any longer flights, but as I was looking at the chart, I realized that Darrington was only about 25 nm away, and I'd never been there before. That seemed like an ideal destination, so I launched and turned northeast from Arlington.

The Darrington airport is a very small strip set near downtown Darrington -- Darrington is a town of about 1400 people, so "downtown" is a relative description. Nevertheless, the airstrip is right in the middle of town. I was interested to see runway lights and a beacon: I had flown (in a different plane) out to the Concrete airport a few years ago hoping to watch a meteor shower from a very dark place, but Concrete didn't have runway lights. Darrington isn't quite as dark, but the ability to actually land at night overcomes that downside to some extent.

The wind was blowing pretty strongly from the west, so I set up for runway 28. I actually overestimated the amount of wind the first time around, and wound up too high to land, so I went around and tried again rather than try to salvage an obviously flawed landing approach. Once I got down, I parked the plane next to a helicopter with a massive boom strapped to the skids, which looked like it hooked up to some kind of geological sensor box. The stamp at Darrington is located in a "small box on the beige hangar" -- with the aid of the photo on the passport website, I realized it was what looked like a discarded electrical junction box. I gathered my stamp and took a few photos. I found Darrington to be a surprisingly delightful little airstrip.

The flight back was not as daunting as I'd feared (I was expecting the headwind coming up the valley to really slow me down, but it wasn't bad), and I realized that it was only 7:20, and I had ages until sunset (8:03 pm), so why not pack Paine Field into the flight? I entered my best powered-descent mode, hitting 115 MPH (normal cruise is about 85, so this is screaming for Norbert) as I made tracks for Paine's traffic pattern.

Once on the ground, the Paine ground controller didn't know about the passport stamp, so I stealthlily looked it up while doing a very slow taxi. I called the ground controller back, and after a few minutes of mutual confusion, they got me directed to the right spot, right next to Regal Air. I leapt out of the plane, ran into the flight planning space, stamped my passport, and dashed out again. Norbert was swung 180° and shuddered to life again -- that sun seemed to be accelerating toward the horizon as a cloud bank suddenly hid it from view, and the moment of sunset is my official cutoff.

Fortunately, there was no waiting to get to the runway, and I was off the ground having only spent about 10 minutes between landing and takeoff -- that's definitely a record for me. I managed to touch down at Harvey with nearly 5 minutes to spare, and relaxed with a celebratory snack as I watched the sky fade from blue to pink to purple over Norbert's nose. I had spent a mere 14 minutes between starting the engine at Paine and shutting it down at Harvey.

Flying continues to be a surprisingly potent source of happiness for me. It finally took finding my own airplane to really get into the groove of things, but I'm glad I did. Now I just have to plan out the next few batches of passport stamps I need to go for...

Posted at 22:48 permanent link category: /aviation

Sat, 23 Mar 2019

Image by Chris

Kennedy, used under CC BY-NA 2.0 license

I found myself with some free time a couple days ago, and decided to take Norbert the Champ up. There was an occluded front due in the afternoon, so I had to abandon my original plan to fly over to Port Townsend (0S9) for a late lunch. Instead, I decided to do some pattern work and possibly some turning-stall work in the practice area. I wanted to stay close to the field so any nasty weather that turned up wouldn't catch me away from home.

According to the new weather robot at Harvey Field (S43), the wind was blowing about 180-190°, and between 10 and 15 knots in gusts. The closest runway is 15L, so there was a bit of crosswind, but nothing terrible. The gusts made things more interesting, but fine practice for me -- I rarely get to take off and land with crosswinds and need all the practice I can get.

One of the members of my EAA chapter has been developing a pretty cool program aimed at experimental (homebuilt) aircraft, to determine and then correct low-speed stall characteristics. Specifically, he's worried about the base-to-final turn, which is the closest to the ground most pilots will ever turn, and thus the one most fraught with danger should anything go wrong. He recently lost a friend to a likely stall-spin accident on a base-to-final turn, so his idea has received fresh momentum.

Something he mentioned recently was that most pilots haven't explored their aircrafts' stall characteristics except the most basic straight-ahead power-on and power-off stalls. Stalls while turning can be very exciting, easily leading to a spin -- a condition which may be unrecoverable at low altitude, and a prolific killer of pilots in the beginning years of aviation. I realized that not only did I not know my plane's behavior in this condition, I'd never done a single turning stall in my entire flying career.

The setup for these stalls is exactly the same as normal stall practice, except the plane is turning. Add at least another thousand feed of altitude compared to normal stall practice, just in case. A spin can develop very quickly, and the extra space gives you a bit more breathing room to recover if it surprises you. It would be best to have experience recovering from spins and recognizing incipient spins before trying this yourself, but read this handy article on spin recovery at a bare minimum. I spent several hours doing spin recovery training with a CFI a few years ago, which makes me barely competent, but I felt safe enough to give turning stalls a try.

The first thing I tried was power-off turning stalls. I figured, correctly, that with less energy involved, things would be a bit calmer. So I set up for my normal descent to landing -- carb heat on, power to idle, and enter a 20-30° bank to turn from downwind to base. Since I didn't know exactly when the stall might happen, I put myself into a constant rate turn, kept the ball centered with the rudder, and pulled back on the stick. With the hand grip buried in my belly (I really need to get rid of that thing; the belly, not the handgrip) and maintaining a nearly 45° bank angle, the plane simply refused to stall. Just to eliminate the possibility that the 7EC Champ is more resistant to turning stalls to the left than to the right, I climbed back up to 4000 feet and tried again, this time circling to the right. Nope, no stall.

Surprised, I climbed back up to 4000 (the Champ didn't seem to be stalled, but it was definitely going down quickly, losing 700 feet in what felt like maybe 45 seconds) to try power-on turning stalls.

This time, I set up for a fairly unrealistic 45° bank coordinated turn at full power, and held the stick full back until I got a definite stall break. To my complete surprise, with the stall, the plane rolled sharply away from the direction of the turn, trying to roll into an opposite-direction turn and possibly stall/spin (I stopped it before it could develop). I tried in the other direction: same thing. Weird.

I haven't yet figured out the aerodynamics of what might be happening with the power-on turning stall, but I was interested to see that it also seems to happen with the 7AC Champ model in X-Plane. My understanding was that X-Plane treats stalls in a somewhat unrealistic manner, since the aerodynamics get pretty tricky around stalls, and it's hard to simulate them properly. It's cool that the simulator mimics real life in this situation.

My EAA member's idea (I'm not naming him because the program isn't official, and I'm not following it, just inspired by the discussion) with his base-to-final stall/spin reduction, as I mentioned earlier, is that pilots of homebuilt aircraft should explore their planes' stall characteristics, including in a turn, like I did. Once it's determined whether the plane wants to drop a wing in a stall (leading to a spin), apply appropriate anti-stall modifications to the wing, such as vortex generators, stall strips, etc. to correct the behavior. This should lead to a safer and more predictable plane. It's a great idea, and I'm glad he's working on it.

I'm equally glad that I tried out a couple of turning stalls to see what would happen in my plane. The results were very surprising to me, both the fact that the plane didn't want to stall in a turn with the power at idle, and the manner in which it stalled with power on. I may spend some time exploring the power-on stall a bit more, to see if I can figure out what's going on with the airflow that causes the plane to flip around like it does. I'll continue flying well away from the potential danger zones of the stall. I'm glad to learn another bit of knowledge about how my plane behaves.

Posted at 23:00 permanent link category: /aviation

Thu, 13 Sep 2018

My work sent me on a trip to Orlando recently, and I checked in with folks on the Biplane Forum to see if there was anyone who's be interested in showing off a project, or if there was some aviatory attraction I should definitely see. I got a few suggestions, but by far the most appealing one was to visit a set of three Chargers at the Ormond Beach (OMN) airport.

My work duties were finished around 5 on the day of my visit, and I was rolling by about 5:20. Unfortunately, from where I was, it would be at least an hour and a half drive, and traffic at 5:20 on a weekday meant there was an additional ten minutes of delay. Silently cursing as I passed through Florida's plethora of poorly-explained road toll booths, I made it to the airport around 7.

I met D., who had made the invitation initially, at the gate, and he introduced me to a crowd of folks, all of whose names have already disappeared from my fickle memory. I think two of them were Charger owners, D. used to own a Charger, and there was one owner who wasn't at this particular event. They were gathering anyway for a birthday celebration for R., who I ended up talking to after my flight.

D. looked up at the sky and said, "Let's get you up before sunset!" We pulled his plane out, and climbed in. I found that I mostly fit in the front cockpit, but the rudder pedals were uncomfortably close. I still managed to fly the plane just fine, but I wouldn't enjoy a long cross-country in the passenger seat.

I had an airspeed indicator, an altimeter, and a tachometer as my instruments; a control stick, rudder pedals, and throttle as my controls. We taxiied out to runway 8, and after a brief run-up, launched into the humid, warm air. D. gave me the plane as soon as we were out of the traffic pattern around OMN, and told me to stay around 1000 feet to keep under the Daytona Class C, and then we could climb once we hit a particular body of water.

We got to our mark, and I sent the throttle forward. The plane didn't scream upward, but it climbed with more vigor than Norbert the Champ would have. Looking out over the short twin wings was a little strange -- Norbert's wings are 5 feet longer in each direction, and there's only the one on top.

I was more relaxed than I had been in the other Charger I've flown in, probably because I was over the first-time jitters. I found that the plane responded quickly to control inputs, and felt like it was shorter in all dimensions than the comparatively pokey Champ, which is true. Ailerons rolled the wings faster, the rudder swung the tail more aggressively, and the elevator pointed the plane up and down with greater speed and less pressure. It also struck home how much more comfortable the stick arrangement is in the Charger: in the Champ, the stick pivots below the floor, and although this is very neat and trim looking, it means the stick swings pretty far in all directions. The Charger has the stick's pivot above the floor, so you can see the workings of the system.

I tried a variety of maneuvers, dancing around the puffy clouds that dotted the sky: a power-off stall, a power-on stall, steep turns, a slip, a dive, etc. The power-off stall was almost shocking in how gentle it was. It wasn't properly a stall at all -- we were clearly going down while aiming up (or at least level), but there was no break, and I had a sense that at least one of the wings was still flying. The power-on stall was much more interesting, breaking distinctly and dropping the left wing promptly. A release of pressure and a touch of rudder straightened the plane back up, and we were flying again. The steep turn was unremarkable and quick. The slip was pretty weird: unlike the Champ, which seems to be designed to slip, the Charger wouldn't plunge over at 45° and drop like a rock. I could get it over about 20° then ran out of rudder, and it didn't seem to go down appreciably faster than just slowing the motor down and coasting downward. I suppose the advantage would still be that you could descent without gaining extra airspeed, but a slip was definitely where the Champ is the more capable plane.

The wind in the cockpit was basically unnoticeable. It was there, and in cold air I would have been cold, but it wasn't howling through or anything. The windshields were a single sheet of (probably) polycarbonate that had been scored through about half of its thickness by a 1/8" or so saw blade, then bent along those scores to form the three-faceted windshield shape I like for these planes. It was an interesting technique that I haven't seen before. It's nice in that it doesn't leave a big distorted section around the bends, and it doesn't require a frame. D. said that the wind in the back cockpit was more present, but not terrible. He was able to turn off the push-to-talk feature of the intercom, and just leave it always-on, so maybe I block the wind more effectively than other passengers. D. said that a front pit cover is a very good idea, and very nice to fly with compared to an uncovered but unoccupied front cockpit.

As the sun descended toward the horizon, we turned back to the airport, and dropped down to get under the Class C again. D. seemed to be offering to let me land the plane, but as we approached OMN, I gave it back to him, unsure which runway we were landing on, and certainly having no experience landing a biplane. In the traffic pattern is a bad time to learn much of anything, and I figured it would be safer all around to give that particular offer a thanks-but-no-thanks this time.

After we were down -- the landing was stiff-legged but not bad, and I could feel the difference between the Champ's oleo gear and the Charger's rubber donut setup -- we taxiied back in, and I had a chance to wander around the assorted Chargers in the hangar. One was missing its motor (I took advantage of the opportunity to photograph the firewall, motor mount, and what accessories were still mounted), and the other was fitted out with a giant Dynon glass-panel screen in the pilot's cockpit, with a very professional-looking black instrument panel. All three Chargers were painted the same scheme of white and red and black checkerboards and sunbursts. It's a good looking scheme, though it looks like it would take a long time to mask off and paint.

I ended the evening talking to R., who built one of the Chargers (I think he built the one that was sitting with its engine removed, but I'm not so sure now). He was the owner of the one D. took me up in, and I got the impression he's been building airplanes for a long time now. We talked about good and bad points of the Charger design. He pointed out a few things that I should address:

- Fix the landing gear -- even with my plan to switch to Grove spring gear, he suggested I should reinforce the longeron they will bear on

- Reinforce the upper wing landing wire attach plates, right where they get welded to the inner hoop; I believe these are parts -203 and -204; apparently they crack under hard acro

- Add 1/8" plywood plating over the wing fuel tanks to increase the strength of the structure

I wish I had had more time to chat with him, but I knew I still had a 90 minute drive ahead of me, and my sleep schedule has been all kinds of messed up lately with the switch from Pacific time to Eastern time plus not sleeping well in the hotel bed. It was after 9 by the time I left, though fortunately the return trip was through much less traffic than the way there. It still took an hour and forty-five minutes to get to the hotel after a stop for gas and slowing down for some torrential rainstorms that passed through.

It was a surprisingly nice visit -- I don't mean that I had expected it to go poorly, just that I didn't have any real expectations beyond that I would see some planes. Everyone was very friendly, and welcomed me as if I've been hanging out with them for years. D. and R. were very generous with their plane and their time, and it was a very kind gesture on D.'s part to let me fly basically the whole flight after takeoff.

I know a few more things to look out for on my build, and I have re-confirmed that the Charger is a nice plane to fly. Being in the 160 HP plane rather than one of the 180 HP planes means I also have a reasonable expectation for how my plane might perform (I'm not planning on using the larger 180 HP motor unless a too-good-to-ignore deal shows up). R. and I exchanged eyebrow waggles and appreciative discussion of putting a radial engine (probably the Verner Scarlett 9S in my case) on a biplane, which would be a 150 HP solution.

So, hooray for unexpected business trips that can be turned to biplanely purposes. I have more information, and another half hour of Charger time in my logbook.

Posted at 10:58 permanent link category: /aviation

Sun, 09 Sep 2018

I recently took a day off work, and decided that I would fly Norbert, my little Champ 7EC, to Yakima. Actually, I decided to fly to Wenatchee, but the runway was closed, so I changed my destination to Yakima. The main reasoning was to try flying over the Cascade mountains, which have formed a real barrier in my mind that was limiting where I thought was a good destination.

The Cascade mountains run north-to-south, east of Seattle, and they form an unbroken chain from British Columbia all the way into Oregon, where they merge and blend with a few other mountain ranges. They're not the 11,000 foot monsters to be found further east in the Rockies, but with many of the peaks topping off between 6,000 and 10,000 feet, they're still nothing to sneeze at.

And they have formed the eastern border of where I was willing to fly in the Champ, which is many fine things, but "fast climber" is not among them.

So, I drove out to the airport, sailing past the grinding traffic heading the other direction, toward Seattle. I arrived at Harvey Field (S43) around 10:15, and preflighted the plane. Plenty of fuel, having tanked up at Arlington's (AWO) relatively cheap pump a few days before. Relatively cheap these days is $5.06 per gallon of 100LL gasoline.

I was floating off the runway around 10:50, a bit later than I'd planned, but not catastrophically so. The path I'd plotted out took me down the Snoqualmie Valley to Fall City, where I would form up over I-90, and fly more or less over the freeway to ensure I'd avoid any dead-end canyons. Once to Ellensburg, turn left for Wenatchee (EAT), with a right turn to Yakima (YKM) presenting a good alternative.

The flight briefer had mentioned that runway 12-30 at Wenatchee was closed, but I didn't take much note of it. The airport symbol at Wenatchee shows two runways, so I figured I'd just land on the one that wasn't closed. I've gotten into the habit of just glancing over the airport information for my destination before I depart, now that accessing the chart and supplement with airport data is so easy on the tablet I usually fly with.

As I was climbing out from Harvey, I called into Seattle Radio and opened my flight plan, also giving them a quickie pilot report about the smoke in the air -- I guessed I could see about 50 miles in haze. The flight service operator repeated the warning about runway 12-30 in Wenatchee being closed, which I thought was odd, but I thanked him and switched back to Seattle Approach to set up flight following (a radar service where they call out traffic they think might conflict with your flight path, and very handy). Fall City's tiny private airstrip passed underneath, and I eyed my chart to make sure I wasn't climbing into the tightly controlled Class B airspace that surrounds SeaTac airport (SEA) even as far east as Snoqualmie.

The fact that the flight services guy had mentioned Wenatchee's 12-30 closure again nagged at me, so I pulled up the airport info for EAT. Oh. There is only one runway at Wenatchee. And it was closed. The second runway shown on the chart is present, and thus visually important enough to depict on the chart, but you're not allowed to land on it. Sigh.

So, I called Seattle Radio again, and amended the flight plan to land in Yakima instead. I had considered Yakima as a destination already, so it wasn't any real mental effort to shift my plans.

By this time, I was nearly to my desired 7500 foot cruising altitude, chosen so that I'd be above the majority of the mountain peaks by a comfortable margin, but not so high that I'd climb into the unfavorable winds predicted at 9000 feet. As it was, I seemed to have no wind at all to contend with, which was nice. The air was smooth, and I placidly watched I-90 wind around under me. Snoqualmie Pass crept slowly past (I was making all of 83 MPH over the ground), looking odd and barren with its ski slopes covered in yellowed grass and empty parking lots presenting appealing emergency landing strips should the engine falter.

Then Norbert and I were on the dry side. The road, I knew from driving it in the past, started sloping down, and the vegetation changed. The big lake just east of Snoqualmie Pass passed by, and the last threat of the mountains faded away. In truth, I never felt like I was flying through mountains, since I'd reached 7500 feet by the time I got over serious mountains, and none of the nearby peaks reached that high. There was probably a 50 mile stretch where finding a good landing spot would have been tough, but never impossible.

Then we were on to the valley that spills to the east from Snoqualmie Pass. I flew over the small airstrips that dot the landscape alongside I-90, spotting some, and unable to see others. De Vere (2W1) in particular evaded my efforts to spot it despite knowing exactly where it should have been. Ellensburg (ELN) was easy to spot, and once I reached it I turned right over the hills to find Yakima.

The advantage of having a flight planned out on the tablet is that you get immediate feedback that you're going where you intended to go. Because it's tracking your travel over the ground, corrections for wind drift are built in by the nature of the beast. I could have planned everything beforehand, and filled out one of the cross-country planning sheets I got when I started flying (and before tablet computers beyond the Apple Newton existed), but it would have meant that when I realized I needed to go to Yakima instead of Wenatchee, I would have had to pull out the chart and do some plotting and calculating to know what compass heading to fly. With the tablet, I just scrolled over to the Route tab, deleted EAT, and added YKM. New line drawn on the chart for me, and I'm good to go. I appreciate knowing how to do it the old way, but the new way is pretty awesome.

It was a short leg to Yakima, and Chinook Approach put me in contact with the tower when I was about 12 miles out from the airport. I could see where I thought it should be, but I knew from past experience that I can very easily get airport identification wrong, so I held off on descending until I was 100% sure I had the airport in sight.

Then, being 4000 feet too high, I had a lot of altitude to lose in a hurry. Fortunately, the Champ is a champ at going down quickly and safely, so I put it into a slip, and flew the plane sideways. We descended over Yakima quickly. I realized at some point that I was smelling gas, which is never a good feeling, and glanced out the side window to see fuel dripping out of the right-wing tank vent. Oops. Straightened out the plane, and thanked past-me for filling the tanks full enough that I wouldn't have any danger of fuel starvation, but also slightly cursed past-me for filling the tanks so full I couldn't slip down to get to pattern altitude.

The tower cleared me for landing, and I touched down on the soverign soil of Yakima International Airport.

I knew from my preflight studies that Yakima didn't hold any appealing attractions for me, which is part of why I'd picked Wenatchee at first. So, I wandered around a little bit, looking for an entrance into the terminal to use the bathroom, eventually being directed to the big, obvious RAMP EXIT sign over a gate far from the terminal. Logical, really, that you'd walk away from the bathroom to get to the bathroom.

Having successfully used Yakima as my biological dumping ground, I checked the weather and the fuel price at Ellensburg, and got the plane back in the air. My plan now was to fly the half hour to Ellensburg and fuel up there for the return trip to Snohomish.

The return trip over Yakima town and the ridge to Ellensburg was uneventful, though I did look down at the smooth, bare ridge and ponder a YouTube video recently pointed out to me of a Kitfox pilot landing on similar hills in Nevada. I didn't ponder it very hard, since the Champ is not a Kitfox, and my little tires are not the giant tundra tires he was sporting, and I had no idea if the land below me was public-use or privately owned. Ellensburg hove into view, and I descended down to the traffic pattern, slotting in behind a twin that was doing touch-and-goes.

After a little musical-chairs action with another pilot who was sitting in front of the fuel pump looking at a phone, I pumped another 10 gallons into Norbert's tanks, and made my way back into the air. I was getting anxious about getting back to Harvey, since I was due to meet with an instructor at 4 to do my Biennial Flight Review.

Oddly, I immediately spotted the wind turbine farm west of Ellensburg as I took off, but completely missed it on the way in. It's a huge, distinctive landmark, and I thought it was odd that I hadn't seen it. It ended up being a useful landmark as well, as I communicated with a plane that was doing maneuvers over it, and we were able to negotiate who would go where by references to it.

Past the wind farm, I started to notice that I was flying the plane a bit oddly. I kept adding way too much right rudder. Norbert normally needs a few pounds of pressure on the right rudder in cruise flight, for whatever reason. So it's a habit to just keep that pressure in, but for some reason, I kept adding way too much, so we ended up flying a bit sideways. I eventually decided it had to be from the quartering tailwind that was speeding me along a little bit, but also causing me to drift to the right over the landscape. Even being conscious of it, I found that I had to repeatedly correct my over-use of the right rudder. Fortunately, the side-wind went away about half-way along the mountains, and I was able to stop worrying about it. Snoqualmie Pass drifted by dreamily and I kept glancing at the Estimated Time of Arrival box on the tablet's display. I was going to be 10 minutes early according to the box, but I knew that maneuvering for traffic patterns and taxiing would eat much if not all of that time.

In light of the comparative rush, I decided to do something unusual. I turned right at Snoqualmie Pass, directing my path of travel right over a tall mountain, but with I-90 and the flat fields beyond the mountain still in gliding range. I had been cruising at 8500 feet (if you're flying east, you fly at odd thousands-plus-five-hundred-feet, and if you're flying west, you fly at evens), and tried pointing the airplane downhill without substantially reducing power. This is unusual, but not wrong necessarily. The plane doesn't seem to enjoy flying much over 100 MPH, but the official Never Exceed speed is actually 135 MPH, so there's a lot of leeway available. Being a 60+ year old plane, I don't like to push it to the point of discomfort, but I figured it couldn't hurt to try. Norbert dove like an expert as I put us into a 115 MPH speed-descent. Of course this all had the advantage of getting me to Harvey Field noticeably faster than my normal 80 MPH cruise speed.

I made it on time almost to the minute, shutting down the engine at 3:59. It's funny how these timings seem to work out. My instructor ended up being a few minutes late in any case, and we had a good BFR, he passing me with flying colors. It helps to have an instructor who's just as finicky as you are.

Interestingly, I am writing this entry from 22,000 feet above eastbound I-90, where was just able to observe the same path that I flew a few days ago, but at several times the altitude, and many times the speed. My two-hour flight to Yakima probably would have taken 25 minutes in an Airbus A320. I prefer the two-hour version in the Little Champ that Could, even if it does shiver uncomfortably when you push past 100 MPH.

Posted at 10:50 permanent link category: /aviation

Thu, 06 Sep 2018

I was flying to Yakima yesterday, talking to Seattle Center, an air-traffic control facility that covers most of the northwest United States. Seattle Center is responsible for the airspace that's not around big airports; you talk to Seattle Approach when you're coming in to SeaTac, you talk to Portland Approach when you're coming in to Portland International, etc., and you talk to Seattle Center once you're outside of Approach's airspace.

As a small plane flying under Visual rules (the big planes are all flying under much more restrictive and communication-required Instrument rules), I talk to ATC mostly so they know where I am in case of potential conflicts, and for the reassurance that someone is paying attention to me if anything goes wrong.

Normally, on the radio with Center, it's all business all the time. You get a lot of exchanges like this, where this is the entire conversation:

Controller: United 123, turn left heading zero-five-zero.

United 123: Left to zero-five-zero, United 123.

It's normal to get a long string of these instructions, so you get used to the rhythm of the language.

Controller: Alaska 234, climb and maintain fifteen thousand, one-five thousand.

Alaska 234: Climb to fifteen, one-five, Alaska 234.

Controller: UPS 987 heavy, turn left heading one-two-zero for traffic.

UPS 987 heavy: Roger, left turn to one-twenty, UPS 987 heavy.

Controller: Cessna 456-Tango, contact Seattle Approach, one-one-niner point two. Good day.

Cessna 456T: Nineteen-two for 456-Tango, good day.

Airplanes are handed off to different controllers by zone, so when you cross from one zone into another, you get passed off to that zone's controller. When you switch frequencies, you check in with the new controller, so they know you're on frequency and talking to them:

Cessna 456T: Seattle Approach, Cessna 456-Tango with you, ten-thousand-five-hundred, VFR.

Controller: Cessna 456-Tango, roger.

So when something unusual happens, it sticks out just because it disrupts the flow. Thus the following incident, which happened more or less like this (details changed because I can't remember them), sticks in my memory:

Santos 123: Seattle Center, Santos 123 with you, ten-thousand.

Controller: Aircraft calling Center, say again the callsign?

Santos 123: It's Santos 123, that's Spanish for "underpaid."

Unexpectedly long pause

Controller: [barely contained laughter] Ok, Santos 123, maintain ten-thousand, expect lower in one-zero miles.

I suspect, unfortunately, that you had to be there, but it was a good joke.

Posted at 10:55 permanent link category: /aviation

Thu, 05 Jul 2018

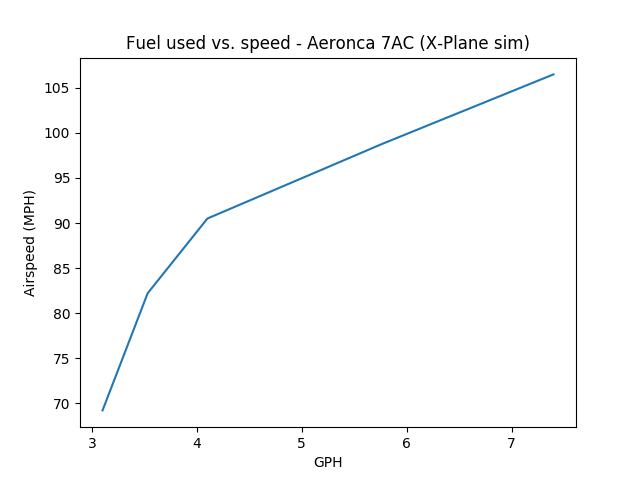

Fuel Used vs. Airspeed (X-Plane edition)

I've been curious for a while to see what the efficiency of the Champ was. How much does engine power buy you speed? What's the most efficient use of fuel vs. travel time?

I don't have a complete answer by any means, but I've collected one form of data:

| Fuel flow (GPH) | Airspeed (MPH) | Miles per gallon |

|---|---|---|

| 7.4 | 106.5 | 14.4 |

| 5.77 | 98.8 | 17.1 |

| 4.1 | 90.5 | 22.0 |

| 3.53 | 82.2 | 23.3 |

| 3.1 | 69.2 | 22.3 |

This data was generated in the X-Plane simulator flying a mostly-accurate Aeronca 7AC model someone made available on the x-plane.org download site. To gather it, I flew at different throttle settings, stabilized the plane so it was flying level, and recorded fuel flow and indicated airspeed. Much easier to do this in the simulator than in real life -- I don't have a fuel-flow meter in real life!

Obviously, this is not Hard Science™. It's still interesting. I only gathered 5 data point over the course of about 15 minutes of flying, but it's representative of the range of speeds you might reasonably fly a Champ. The fuel flow numbers are at least similar to what I would expect in reality, though the RPM indicated for a given fuel flow is substantially high compared to what I see in my own plane.

The Champ instrument panel in X-Plane

The conclusion that I see here is obvious: if you're flying a digital Champ in X-Plane, and you have the same model of 7AC I downloaded, aiming for a cruise of about 83 MPH will get you the best fuel efficiency. Pretty much squares with what I see in the real world.

It'd be neat to some day instrument the plane to duplicate this test in real-world conditions, though I doubt I will. Fuel flow meters are expensive, and somewhat counter to the feel of the Champ. If I could do it temporarily, though, that would be very interesting...

Posted at 23:04 permanent link category: /aviation

Wed, 13 Jun 2018

Back in February of last year, I got a plane. Norbert, the Champ. I was (and still am) an active member of Chapter 84 of the EAA. EAA 84 has their chapter meetings on the second Tuesday of every month. Now that I owned a plane, I really wanted to fly it to one of these meetings.

The problem is, Chapter 84 meets in Snohomish, at Harvey Field (S43), the same airport where the plane is based. It doesn't make much sense to fly the plane to its own airport. How would that even work?

It works if you're a bit crazy. Crazy like a crazy person!

It goes something like this: very early in the morning, drive up to Snohomish, conveniently going the opposite direction from all the traffic. Get in the plane, and fly it from Snohomish to Boeing Field, which is reasonably close to downtown Seattle, where I work. Take a taxi (since there is no practical bus service) to downtown. Work for the day. Leave a touch earlier than normal, and take a taxi back to the airport. Fly from Boeing Field to Harvey Field, waving slightly ironically at all the poor car commuters below me on I-5, moving through a 10 MPH continuous traffic jam. Go to the meeting. Drive home. Simple, right?

As simple as it should be, the Seattle weather and my schedule have conspired for well over a year to prevent it from happening. If I can go to the meeting, the weather is terrible. If the weather is gorgeous, I'm otherwise committed. Most vexing.

Finally, yesterday, I was able to pull off the World's Silliest Commute™. The weather was predicted to be perfectly flyable until midnight, well after I needed to fly.

I should note that I live about 6 miles from my workplace. A bike trip takes 35 minutes each way. Taking the bus takes 35-45 minutes depending on traffic.

Getting There

So, I left the house at 7 am almost on the dot. I arrived at Harvey Field without much incident 45 minutes later. There was a car fire that was out at Northgate, which slowed everyone down so they could rubberneck at the flashing lights, but that only added a minute or two to the trip. So far so good. I preflighted the plane, and was in the air by about 8:20. I shut down at Boeing Field half an hour later, at 8:49. So far, so good!

The weather was gorgeous for the flight in

I parked the plane at Kenmore Aero Services, who charged me the princely sum of $15 in "handling" to stay there for the day. Cheapest parking on the field, though, and compare that to a day of parking your car anywhere near downtown ($30+). Parking for airplanes is weird.

Anyway, I called a cab, who showed up about 9:05, and we were on our way. Unfortunately, Airport Way (the most logical path to downtown) was blocked, and we had to backtrack and take a very crowded I-5 to get there. I arrived at the office around 9:40. Fortunately my workplace is very chill about when people show up.

So, trip to work: two hours and 40 minutes. Pretty clever, eh!? Also, $15 parking, and $40 for the taxi. Also, 27 driving miles and 24 flying miles.

My plane-a-day calendar was, happily, an Aeronca Champ!

The trip back was even better.

Getting Back

The taxi ride was about twice the cost I'd been anticipating, so I was somewhat anxious to avoid having to take a taxi back. Spending another $40 wouldn't kill me, but it wasn't very appealing either. I've never signed up for Uber or Lyft, so I figured I'd check out taking a bus to close by, and then using one of the rental bikes that litter the city to make the final stretch. The buses run to the north end of the field, but then they divert down the west side, and I needed to go to the east side, which would be a long walk from the nearest stop.

I identified the route: Metro 124 goes right past, and was the obvious choice. I tried signing up for Limebike (one of the rental bike outfits), and was dismayed by the terms I ran into: the Lime app won't even show you the map unless you've got location (GPS) turned on -- which I don't normally do, since I try to limit data leakage. It appeared from the non-existent documentation (ie, how the app behaved) that I would have to load a minimum of $10 into my account, but I have no plans to use these bikes long-term. Overall, the experience left me very unhappy with how it worked, and kind of turned off from the whole idea.

I looked back at the bus route, and realized that A) I needed to go to nearly the southern extremity of the field, and B) there was a bus stop on the west side of the south end of the field. It would only be about a 20 minute walk from the bus stop to Kenmore, vs. the 45 minute walk from the north end of the field (Boeing Field's long runway is about 10,000 feet long, or nearly two miles long; the surrounding land is over 2 miles long). Sold!

So, I left the office early, at 3:45, and grabbed myself a sandwich to eat for dinner once I'd arrived. I caught the 4:03 bus, and we were off. Then we hit Georgetown, and about 20 minutes of unexpected traffic. One of the other riders complained about the slow pace, and how she was going to spend her entire day just getting home. When I finally arrived at my stop, it was 4:48, making it almost exactly a 45 minute ride.

The walk around the south end of the field and up to Kenmore's building took 20 minutes, with a slight delay while I called to get the weather briefing, staying away from the very loud traffic on Airport Way S. I reflected, as I was walking along the 9" wide path through the grass on the side of the road, how oddly happy I was -- it was delightful to be doing something so different from my normal routine, even if it was kind of weird.

Kenmore was pleasant to deal with, and I fired up the engine around 5:20. Boeing ground sent me to the long runway (Boeing Field has two runways: the 10,000 foot runway, and a 3700 foot runway; the 3700 foot runway is 3000 feet longer than I need to take off), which I found fairly delightful. The Champ is an impressive aircraft in some ways. One of them is its take-off performance: 300-400 feet on the ground under conditions like this. The weirdness of having 8000 feet in front of me (leaving from part-way down the runway, at the A10 intersection) was wonderful. I could take off and land several times in that distance.

Flying past downtown Seattle

Norbert the Champ revved up, and we were quickly off the ground, passing through 100 feet as the control tower went past on the left -- it takes off quickly, but it doesn't climb very fast, with all its drag and its small 90 HP engine. We continued straight out, flying over all the Imperial Walker-looking loading cranes on the waterfront, and past the jeweled splendor of downtown's many skyscrapers. I flew over my house in Ballard just for fun, then angled my path northeastward toward Harvey Field.

As I crossed I-5, I looked down benevolently on the poor suckers in their cars, grinding slowly northward. Normally, that's where I'd be, and the difference again delighted me. It's amazing how often the weather screws up my plans to fly to the EAA meeting.

Crossing over I-5's packed traffic

The rest of the trip was uneventful, and I dropped down to land at Harvey Field, shutting off the plane around 6:15. I quickly tucked it away in the hangar, and was to the meeting by about 6:30. Later than I'd wanted to be, but the bus trip had taken longer than I thought it would.

If you're keeping score at home, that's two and a half hours from downtown Seattle to Snohomish -- and I still had another 50ish minute drive home after the meeting.

The Final Score

On the way in to work, on a normal day:

- Distance (bicycle): 6 miles

- Time: 35 minutes

- Cost: $0

On the way in to work, yesterday:

- Distance (motorcycle): 27 miles

- Distance (airplane): 24 miles

- Distance (taxi): 10 miles

- Time: 2 hours, 40 minutes

- Cost: About $65

On the way home from work, on a normal day:

- Distance (bicycle): 6 miles

- Time: 35 minutes

- Cost: $0

On the way home from work, yesterday:

- Distance (bus): 9 miles

- Distance (airplane): 24 miles

- Distance (motorcycle): 27 miles

- Time: 3 hours, 10 minutes

- Cost: About $10

Total for the day: 121 miles in 5.8 hours: about 20 MPH average, and $0.61 per mile.

Of course, what's not calculated there is how much fun I had doing it. Aside from the patent silliness of what I was doing, I was having a good time the entire time. Even grinding through I-5 traffic in the morning in a taxi driven by a guy who spent more time looking at his phone than at the road was fun, if only in how different it was from my normal daily routine.

In short, it was a good, lightweight adventure. A thrilling change from the normal day-to-day. I'm not likely to do exactly that thing again unless I can figure out a better airport-to-downtown link, but I'm very glad I finally accomplished it after dreaming about it for so long.

Posted at 00:00 permanent link category: /aviation

Wed, 21 Mar 2018

If you like real-life adventure stories and are like me, you've probably heard of The Long Way Round, in which Ewan MacGregor and Charlie Boorman ride motorcycles from London to New York by going east instead of west.

But have you heard of the other Long Way Round? It's the story of a Pan Am Clipper crew in 1941 who found themselves caught up in world events in a way they never saw coming.

Read it here: The Long Way Round: Part 1

Posted at 09:41 permanent link category: /aviation

Tue, 02 Jan 2018

For my New Year's Day, I took advantage of surprisingly good weather, and went flying. It wasn't any kind of grand flight, just up to Bellingham and back (a bit less than an hour each way). It was a good make-up for the previous day's attempt, where we got off the ground for just long enough to make a slightly uncomfortable pattern before landing again under clouds that were much lower than they appeared to be from the ground.

On my two year-spanning days of flying, I encountered two other pilots who stand out in my mind. Unfortunately, they don't stand out for good reasons.

The first pilot is a gent with a Cessna 150. I encountered him while fuelling up my plane. He'd parked his 150 relatively far from the pump, and the ground wire reel got tangled, so that he had the wire stretched to where it just reached his tie-down bolt. We were both setting up to fuel at the same time, and he had some trouble with the card reader. Once he got that sorted out, he pulled out a length of hose, and started fueling up.

Unfortunately, he hadn't gotten the hose retraction reel to a locked position (it's one of those spring-powered reels that goes click-click-click-pause as you unwind it, and you have to stop in the middle of the clicks if you want to keep it from retracting). It started retracting as he was atop the ladder, concentrating on working the nozzle. It didn't seem profitable to let that situation continue, so I grabbed the hose and pulled it out until it locked. I didn't have the impression that he noticed.

When he started his motor, it roared to life with a lot of throttle, then he pulled it back down, and taxied off to run up. I had the impression at the time, and remarked to my passenger, that he seemed like a pilot who was badly out of practice.

I ran into this same gent the next day, and confirmed my impression. He engaged me in conversation, and mentioned that he'd wanted to fly to a nearby airport (about 15 minutes' flying time away), but couldn't, because he couldn't sort out the radios. The aiport we were at, and the airport he was flying to, are both untowered fields, which 1. have no requirement for any radio use at all (though it's a good idea) and 2. need only one frequency change if you do want to use the radios. Most aircraft radios are very simple to use, with a knob to change frequencies, and a volume control, and maybe an audio panel if you have multiple radios. The audio panels can be opaque in their operation, but the 150 has never had very complex equipment.

Based on all this, I would be surprised if he's flown with an instructor in years. That's a bit of a problem, because you're required to do a biennial flight review every two years. I can't imagine the instructor who would have signed off on a pilot who couldn't operate a radio. The requirement for a BFR is relatively buried in the rules, and there are certainly pilots who fly for decades without them, but if anything goes wrong, you can bet the FAA will hike up its eyebrows and tick a couple extra boxes on its clipboard when it finds out, and the slacking pilot will feel the sting.

If this sounds more like you than you'd like to admit, you might check out AOPA's Rusty Pilot Program. I'm all for getting back in the game. But don't endanger other people in the process.

Pilot #2 seemed much more competent, but embodies a type of pilot who gets right under my skin: the "Those laws don't apply to me" pilot. We met while (again) refuelling, and admired each others' planes. He had a similar vintage plane to my Champ, and we got to discussing lighting requirements. I had just landed to avoid flying after sunset, since my plane is not (yet) equipped with anti-collision lights, and he was obviously prepping to launch. He mentioned, "Oh, my IA [highly-qualified airplane mechanic who should theoretically know all the applicable regulations] said I don't need strobes." He explained that, because his plane was made before the 1971 anti-collision-light law mentioned in 14 CFR 91.205(c)(3), it was exempted.

This is an area of aviation law that I'm intimately familiar with, because I want to be able to fly at night, but legally can't due to this missing anti-collision light issue. There's no profit in telling someone that he's wrong, so I mentioned only that I had understood the law differently, and hoped his IA was correct. I had called the FAA district office last summer, and asked this exact question; the answer was unequivocal: no aircraft may operate after sunset without flashing anti-collision lights, period, the end. There is no grandfather clause, as there so often can be with this kind of law.

So I wish him luck in his night-flying, and hope that his position lights are enough to keep him out of trouble. I honestly have mixed feelings about this particular regulation. On the one hand, flashing lights are certainly more visible. On the other hand, they don't seem sufficiently more-visible than steady position (red/green/white) lights as to require all planes ever to have them for night flight. This opinion is certainly a bit selfish on my part, because it's going to take hundreds or thousands of dollars and a bunch of work to set my plane up with the right lights.

What I can't get behind is pilots who act as if the laws we've agreed upon shouldn't apply to them. What else doesn't apply to them? When will it impact someone else? I know we're all guilty of breaking laws on a more or less constant basis (when was the last time you drove over the speed limit, or didn't come to a complete stop at a stop sign?), so I can't get too high-n-mighty about this, but I hold pilots, including myself, to a higher standard. You have very few chances to mess things up with an airplane before the stakes become life-or-death. Why start out every flight with a deficit?

Posted at 10:40 permanent link category: /aviation

Fri, 27 Oct 2017

I decided, in the face of glaringly sunny and clear skies, that today would be a good day to burn a vacation day and go flying.

So, I got up at my usual time, but made a leisurely departure of the house, finally driving off at about 9 am. I knew that Harvey Field would be socked in with morning fog, so there was no need to rush, but also that the sooner I was there and all pre-flighted, the more quickly I could leap into the sky when the fog burned off.

Thus, I had my pre-flight inspection done by about 10:30, but the fog had other plans. I ended up spending an hour in the FBO's plush chair reading my book (nunquam non paratus -- "never unprepared" after all) while the fog slowly dissolved. At 11:30, it was just about burned off, and I made my leisurely way back to the hangar. This was the beginning of the problem.

On my way to the hangar, I pulled out my phone to check in to the FATPNW group page on Facebook, to see if anyone else was planning aerial shenanigans today that might be fun to join in on. I had been pondering a flight around the Olympic Peninsula, or up to Eastsound on Orcas Island, but hadn't made any firm plans yet. There was indeed a post right near the top: several folks were planning on meeting at the Jefferson County International Airport (0S9), also known as Port Townsend, for lunch. That sounded good to me, so I set my sights on 0S9, although I knew from the start I couldn't possibly be there at noon. It was already 11:45 by the time I pulled the airplane out of the hangar, and I still needed to get fuel. So much for getting the preflight done early.

I taxied over to the fuel pump and added 10 gallons to the tanks. I had 9 already on board, and with the extra 10, I would have a guaranteed ~2 hours of fuel that I knew I'd just pumped in, plus some extra from the 9 (never take the dipstick reading at face value -- it's always off by some amount). I was trying to move quickly so I wouldn't be too late to the lunch, but I was trying for "efficient" rather than "rushed."

I didn't actually push back and fire up the motor for real until a couple minutes before noon. It would be at least half an hour's flight to Port Townsend, possibly a bit more, so I was guaranteed to be 45 minutes late after all the taxi, run-up, travel, and tie-down once I'd arrived. Even so, I was trying to keep efficient, since it would at least be nice to say hello in passing.

The run-up was normal, though the engine was a little off for the take-off and climb out. Not enough to cause me worry, and it picked up to normal once it warmed up a little bit more. I got myself cleared over Paine Field, then called up Seattle Approach to get flight following, and have some extra eyes on my sky.

The transit and landing were normal and unremarkable. I tied down, and had a good lunch, packed into a stool at the crowded bar. I wasn't the only one who thought skipping out on work to go flying would make for good lunch plans.

I got myself back out to the plane, belly pleasantly full of sandwich and marionberry pie, and started through the preflight: fuel on, check fuel drains for water, dipstick into the tanks to check level... Wait a minute. The right tank was normal, but when I got to the left tank, there was no gas cap.

This is approximately a Level 4 Oh Shit moment, on a scale of 10. Missing gas cap is embarrassing, because it means I was more rushed than I thought when I fueled up back at Harvey. But it also means (I confirmed a few minutes later on my walk-around) that the low pressure on top of the wing was sucking fuel out of the tank and scattering it to the wind, coincidentally leaving some tell-tale marks on the tail that confirmed the story. It also also means that, somewhere at Harvey Field, hopefully, hopefully, fingers crossed, nowhere near the runway, there was a ¼ pound piece of metal and rubber on the ground, ready to be kicked up by some passing airplane and potentially do some real damage.

So, this was bad juju. I was embarrassed, and scared, mostly because I was worried I'd dropped it where someone else was going to run it over at high speed, which conjured up all kinds of bad images in my head. I dipped the tank, and I still had 14 gallons between the two tanks, so I didn't lose too much fuel on the flight over. Maybe 2-3 gallons. Annoying, but not world-ending.

I had to find something to cover the tank opening with, but that was easily done by approaching the first mechanic I could find and begging a ziptie so I could fasten a nitrile glove over the opening for the flight home. Not terribly practical for everyday use, but enough to fly home safely.

No issues getting back to Harvey, and the instant I had the plane back in the hangar, I went for a walk to find the missing cap. I started by the fuel pump, hoping it just dropped there, which would be fairly safe. No luck. I asked the fuel truck guy, who happened to be driving by, if he'd seen a fuel cap on the ground, but he hadn't. I disconsolately walked along the taxiway, scanning as I went, distantly thankful that there wasn't more traffic trying to use the path. I did a full search grid over the run-up area, figuring that if it had miraculously ridden the wing all the way there, that's where it would be blown off, but no luck. I walked the entire length of the runway, where I located and removed a very sharp stainless steel #10 sheetmetal screw, but no sign of my gas cap.

I realized, as I was halfway down the runway (walking well off to the side, and constantly scanning for aircraft traffic, I'm not always a complete dummy) that I should check in to the maintenance office, on the off chance someone spotted it and turned it in. As I got to the north end of the runway, and turned toward the skydiving area, one of the skydiving folks walked toward me with that purposeful stride that says, "I'm going to challenge your right to be where you are." I quickly explained my situation, and she relented, telling me the tale of a dog-walker she encountered once, who nonchalantly walked his dog across the runway without apparently being aware of what he was doing.

I stopped in to the maintenance office, and before I could say anything, the woman behind the counter said, "Oh Ian, did you get my voicemail?" I gave her a dumb look and said, "Voicemail?" "Yeah," she responded, "someone turned in this gas cap and we thought it might belong to your plane..."

So, I was saved from the worst consequence of someone hitting my gas cap at high speed and causing real damage. I'm glad it fell off right at the gas pump like I'd first expected, and that it was quickly removed to safety. I'm glad I didn't have to rummage around for the spare gas cap that lives somewhere in the hangar.

I decided that I need to find a better place to stick the cap when I take it off to add fuel. I have two choices lined up to try out: one on the engine cowling, so that it will be obvious from the cockpit, and the other in my pocket, so that at least if I forget it, it won't cause anyone else any problems (and I can put it back on when I realize my mistake). I like the cowling idea better, but between the two I'm likely to have a good solution.

It occurred to me as I was walking the airport with my eyes down to the ground that I was lucky in another way: if I'd made the same mistake when intending to fly around the Olympic Peninsula, it could have easily killed me. Extrapolating from the actual fuel consumed on my trip to Jefferson County, I was losing about 4 gallons per hour extra from the tank. Presumably it would go faster if it was fuller, and slow down as it emptied out, but let's call it 4 gallons per hour on average. This plane only uses about 5-6 gallons per hour in normal operation, so I would nearly double my fuel consumption and be completely unaware of it. If I planned on having 4 hours of fuel on board, I would be in for a rude shock at about the 2 hour mark. The plane still glides with the engine off, and I tend to fly high, so I'd have some altitude to spend. But the peninsula is not full of friendly places to land, and my embarrassing error could easily have turned into a fatal one.

So, ultimately, I must both thank and curse FATPNW: without it, I probably would have felt less rushed, but I also would have been in for a longer flight (the path to Orcas is about twice as long as that to Jefferson County). I'm very glad it worked out the way it did, but I've clearly got some reforms to make in my refuelling practices.

Posted at 23:46 permanent link category: /aviation

Mon, 09 Oct 2017

I took the opportunity last Sunday to enjoy the sunny weather from aloft, and went flying in Norbert the Champ.

I put the dipstick in the tanks, and decided that I had about 12 gallons of fuel. Plenty for the ~1 hour flight I had in mind, and it would put me in reasonable territory to drain the tanks and re-calibrate the dipstick, which had seemed a little off when I was trying to work out the math between fill-ups and gallons per hour on recent trips.

The flight went as planned, and I set up in the hangar to drain the fuel from the tanks, eventually (holy buckets does it take a long time to drain a fuel tank by the sump drain) getting about 4 gallons out of the two tanks. Given that I had just flown 1.4 hours at ~4 gph, that already suggested I was on the right track: I should have had about 6 gallons left, not 4.

The tools I had at my disposal were two 6-gallon jugs, and a "2 gallon" jug, which I decided would be my measuring container. It turned out, half way through, that it's actually a "2 gallons and 8 ounces" jug, intended for mixing 2-stroke oil with gasoline, so my measurements were on the imprecise side. I also had the magic hydrophobic funnel, which allows me to do all this fuel pouring without transferring water or other crud.

The fuel system on the Champ is very simple: two 13 gallon tanks reside in the wings, and are connected together above the fuel shutoff valve. This means that they (very slowly) cross-feed at all times, so any fuel additions would have to be to both tanks before taking a reading, to ensure I wasn't seeing one tank slowly creep up the level of the other.

The plan was this (and it worked reasonably well): go to the pumps and fill the two 6-gallon jugs with exactly 10 gallons of fuel, 5 per jug. Fill the 2-gallon jug twice, and fill each tank on the plane with 2 gallons of fuel. Dip the tanks, and mark where the fuel hit, having previously erased the old marks. Lather rinse repeat until the 10 gallons are in the tanks, then go fill the two 6-gallon jugs again and repeat the whole process.

Since I started this exercise with about four gallons of fuel, I first poured this amount into the tanks, and got my first surprise. The right tank registered about an inch of fuel on the stick. 2 gallons, marked and done. The left tank left the stick completely dry. No 2 gallon mark. (The landing gear on the left is always extended slightly further than the gear on the right, so that the left wing is several inches further from the ground at rest.)

Keep going: 4 gallon marks for each tank -- one side of the dipstick is marked RT, and one is marked LFT, but previously, the levels had been exactly the same on each side; don't ask me why there were two sides before. Interestingly, the 4 gallon mark for the left side was only about 4mm below the 4 gallon mark for the right side, suggesting that at 2 gallons, the left tank was just barely shy of hitting the stick.

So I kept going, marking 2, 4, and 6 gallons, then marking 7 when I split the final 2-gallon jug between the two tanks. I went back to the pump, and refilled with another 10 gallons, figuring I was already half-way there, so I might as well finish the job. Marked 9, then 11 gallons, although the right tank overfilled and spilled down the wing by some amount, so the final count was not terribly accurate. Presumably, the tilted wings mean that it would be possible to fill the right tank so far that it comes out the vent, when filling the left tank to the very top.

In all, I put in around 24 gallons of fuel (exactly 20 from the pumps, and about 4 that had already been there, minus the overfill), and completely filled the right tank, while the left tank got near the filler neck but didn't quite touch it. The dipstick reads about a quarter inch difference between the right and left tanks, and had been reading almost two gallons too full on the right tank, and about one gallon too full on the left.

That means I had previously thought I had half an hour more fuel than I actually did. That's a sobering error, and one that could have bitten me badly. It's a more than 10% error.

Since the 2 gallon jug was actually more than 2 gallons, and I didn't fill it to exactly the same amount each time, I'm still only going to trust the dipstick as an approximation of the fuel left in the tanks. It's a more pessimistic approximation now, though, and that suits me just fine.

Until I can redo the job with a properly calibrated filling rig, I'll live with the knowledge that I may have a little bit more fuel than the dipstick says I do, but do the math as if I don't. It's always a better surprise to find out you have more fuel than you think you do, rather than the other way around.

Posted at 21:54 permanent link category: /aviation

Sun, 24 Sep 2017

Last Christmas, I got a Stratux box as a present. This is a little Raspberry Pi tiny-computer with a couple SDR dongles attached, which will listen to aicraft traffic and show it on a tablet. But if you needed that introduction, you can definitely skip this entry, for it will go Deep Nerd on the Stratux, and be incredibly boring for you.

My particular Stratux was running version 0.8r-something (I forgot to note exactly which version it was). It worked pretty well, but on the last few flights, it started doing this thing where it would stop sending traffic to the tablet. If I pulled the power and rebooted it, it could come back for a period of time, but never for terribly long.

So, I decided I would try loading current software on it. The Stratux project is up to 1.4r2, which is a pretty substantial leap. I downloaded the upgrade script for 1.4r2, and sent it in via the Stratux web page. Once I re-joined the wifi network, all appeared to be working, so I tucked it back into the flight bag, and brought it with me for today's flight.

It all seemed to be working for the first maybe 20 minutes, but as soon as I was done with my pattern work and departed for Jefferson County to see if they had any pie left (gotta have some kind of goal, right?), I noticed I wasn't seeing traffic again.

Sighing a bit, I pulled the power and plugged it back in again, wondering if I had burnt out some part of the hardware. It wouldn't be the end of the world if I had, but how annoying. However, it didn't come back. In fact, the wifi network didn't show up again either. That was weird. Made troubleshooting harder too, since I didn't have any other way to access the Stratux than wifi.

I tried a few more times on the way to and from JeffCo, but didn't have any luck. This was just kind of piling on, since I'd already blown 40 minutes trying to retrieve a pen that mysteriously ended up in the belly fabric under the cockpit (a royal pain to deal with, and had me seriously considering whether I'd have to bring in a mechanic to solve it), and discovered that my inexpensive endoscope camera had mysteriously died between the last time I used it and today, when I really wanted it to be working, so I could locate that stupid pen. (I did ultimately get the pen out, by locating it through primitive tap-based echolocation on the fabric, then tapping it so it ended up in a spot I could reach past the baggage area.)

Anyway, discouraging to have all these things going wrong, seemingly all at once.

I brought the box home, and found some information, which I thought others might enjoy seeing as well.